Guide To Eye Health For Women and Girls

The burden of avoidable blindness remains higher for women who represent about 56% of the world’s 36 million blind.[1]

To address this gap, eye health programming practitioners employ various approaches and tools to achieve gender-responsive approaches to programming. However, there is limited evidence of what interventions actually work in gender and eye health and what best practice looks like.

In collaboration with 11 other eye health organisations (Laico/Aravind, KCCO, Orbis, Brien Holden Vision Institute, Seva Canada, Pathfinder International, Nari Uddug Kendra (NUK), Sightsavers, Vision 2020 Australia, and The Fred Hollows Foundation), we have created a Gender Guide for Eye Health Programming to assist with furthering our knowledge of best practice in this area.

You can download the guide here.

What is the gender guide for eye health programming?

This guide presents a set of guiding principles for good practice when it comes to gender-targeted and gender-mainstreamed projects. It is complemented by 11 evidence-based case studies that were developed in close collaboration with the organisations whose work is featured in the case studies. Each case study illustrates good practice to reduce gender inequity in eye health under the WHO health system strengthening pillars.

Why was it created?

There is limited evidence of what interventions are ‘best practice’ or ‘proven practice’ in gender and eye health, which leaves program practitioners in the field unable to confidently apply evidence-informed interventions addressing the gender gap in blindness. This guide presents the existing evidence and principles for gender-responsive eye health programming. This is supplemented by a summary of ‘good practice’ case studies gathered from the collective knowledge of eye health development actors.

Who created it?

The development of this guide was led and coordinated by The Fred Hollows Foundation (Christina Roger and Camille Neyhouser) in close collaboration with 10 other eye health organisations (Laico/Aravind, KCCO, Orbis, Brien Holden Vision Institute, Seva Canada, Pathfinder International, Nari Uddug Kendra (NUK), Sightsavers, and Vision 2020 Australia).

What are the key concepts that this manual discusses?

It discusses the concepts of gender equality and gender equity, and how they can be applied in eye health programming. It provides guidance for both projects that are gender targeted and those including gender-mainstreaming measures.It touches on intersectionality of identities and the cumulative barriers some women are faced with (gender, age, disability, living in a remote location etc).

Each case study illustrates good practice to reduce gender inequity in eye health under the WHO health system strengthening pillars (service delivery; workforce; data and information; infrastructure; financing; leadership and governance).

Why is gender equity important in eye health care?

A gender equity approach “recognizes that women and men have different needs, preferences and interests and that equality of outcomes may necessitate different treatment of men and women.”[2] This is because achieving a fair distribution of the resources and benefits of development may require different treatment of women and men, girls and boys in the way projects are delivered.

With this in mind, targeting women purposely may be necessary to help them overcome barriers that specifically affect them. As the burden of avoidable blindness remains higher for women who represent about 56% of the world’s 36 million blind[3] than for men, we need to implement interventions that specifically tackle the barriers faced by women experiencing avoidable blindness and visual impairment in order to address this gap.

What is the current situation in terms of gender inequality in eye health care?

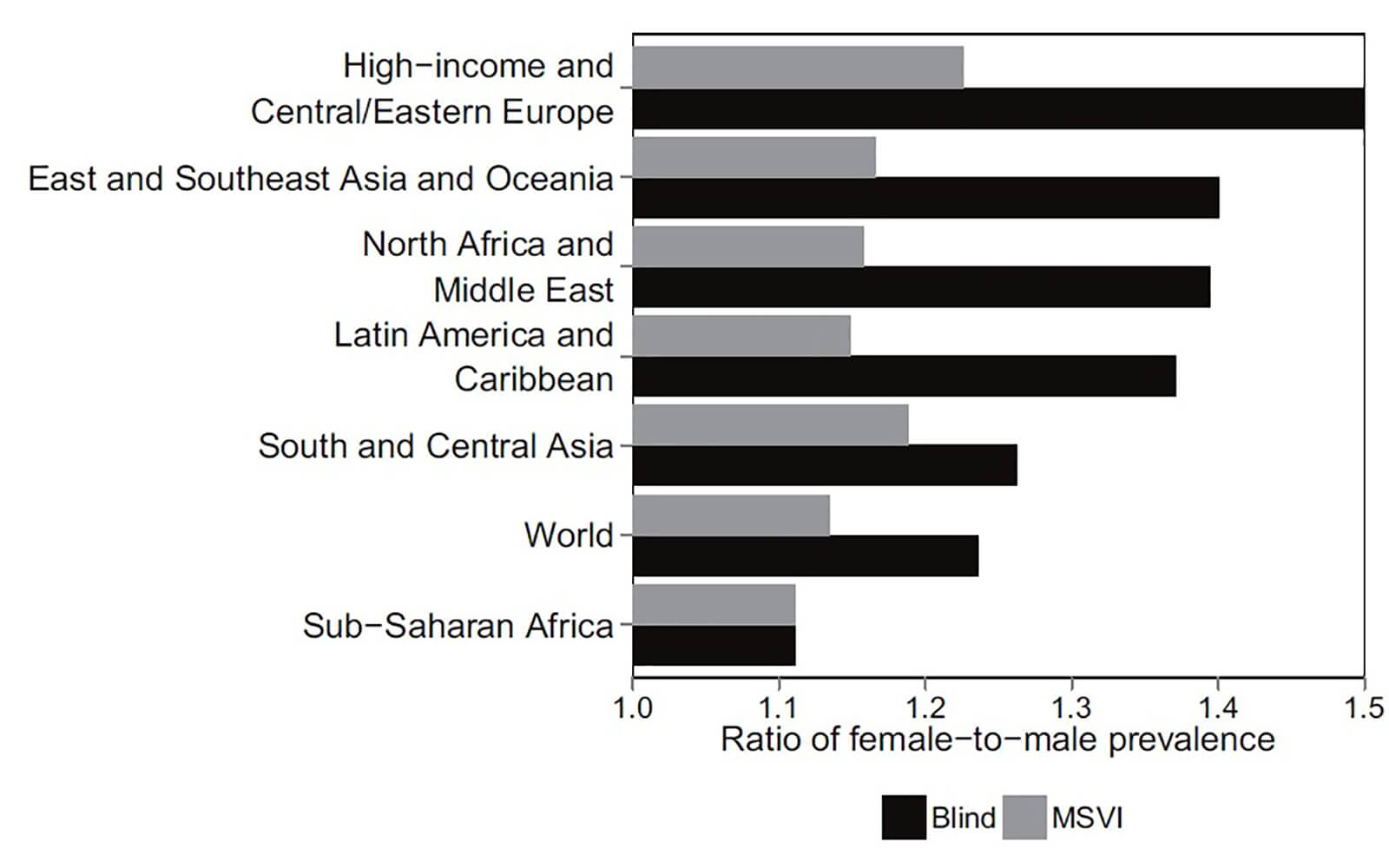

Evidence suggests that in all regions of the world and at all ages, women are significantly more likely to be visually impaired than men[4][5]. Women represent about 56%5 of the world’s 36 million blind5 and 55% of the world’s 216.6 million people with moderate and severe vision impairment (MSVI)[6], yet are the least likely to receive treatment as they face both increased risks for developing blindness and barriers to access[7]. This gender and eye health disparity is characterised by being: found globally, found in the contexts of all treatable eye conditions, and often even larger at a young age.

What can be done about the current situation?

Eye health programming practitioners need to become familiar with and apply various principles and tools to achieve gender-responsive approaches to programming. However, to provide them with the information they need, evidence of what works for gender equity in eye health programming needs to be generated. This guide is a step in the right direction but a lot more research is needed to confidently establish ‘best practice’ in gender and eye health. There is an urgent need to carry out implementation research providing evidence of what works in gender and eye health programming in a range of contexts in order to inform future interventions. Based on this future research, the development of a comprehensive list of factors contributing to the disparity between women and men’s attainment of their full eye health potential and how to address them in each context should be developed.

What information will the reader find in this guide?

1. Introduction

- Key concepts

- Why is gender equity important in eye health care programming?

- The status quo

2. Guiding principles for gender equity in eye health programming

- What are gender-mainstreamed and gender-targeted projects?

- General principles to developing and managing gender-responsive projects

- Conducting a gender analysis

- Identifying barriers

- Specific ways of integrating gender equity into eye care projects

- Checking that your project design is gender responsive

3. Case studies

Download your copy of the guide here

Related articles

Disability data in eye health

Report: Addressing the needs of older people with disabilities