When Eye Care Is Out of Reach, Blindness Follows

From remote villages to city outskirts, eye care is out of reach for most. Women, older people, and those in poverty are hit hardest.

Eye care is out of reach for many people

Millions of people in Nepal, like Krishna, live in remote or rural areas. Without local hospitals or clinics, they are unable to access eye care before it’s too late. A simple cataract becomes permanent blindness.

The rate of blindness is alarmingly high

More than 93,000 people in Nepal are blind. Over 1.1 million have vision loss. Women over 50 are most affected. Cataracts are the leading cause — and 84% of blindness in Nepal is avoidable.

There are not enough specialists

Nepal is home to 29.6 million people, yet there are only 16 ophthalmologists working in public hospitals. To meet even the minimum standard of care, the World Health Organization recommends at least 120 ophthalmologists. Right now, people are going blind simply because there’s no one available to treat them.

We have big goals for Nepal. With your help, we can reach them.

Together with the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, this year we are working to:

- Screen more than 187,000 people

- Perform over 3,700 cataract surgeries

- Provide over 39,000 treatments

- Train more than 560 people, including community health workers, nurses and surgeons

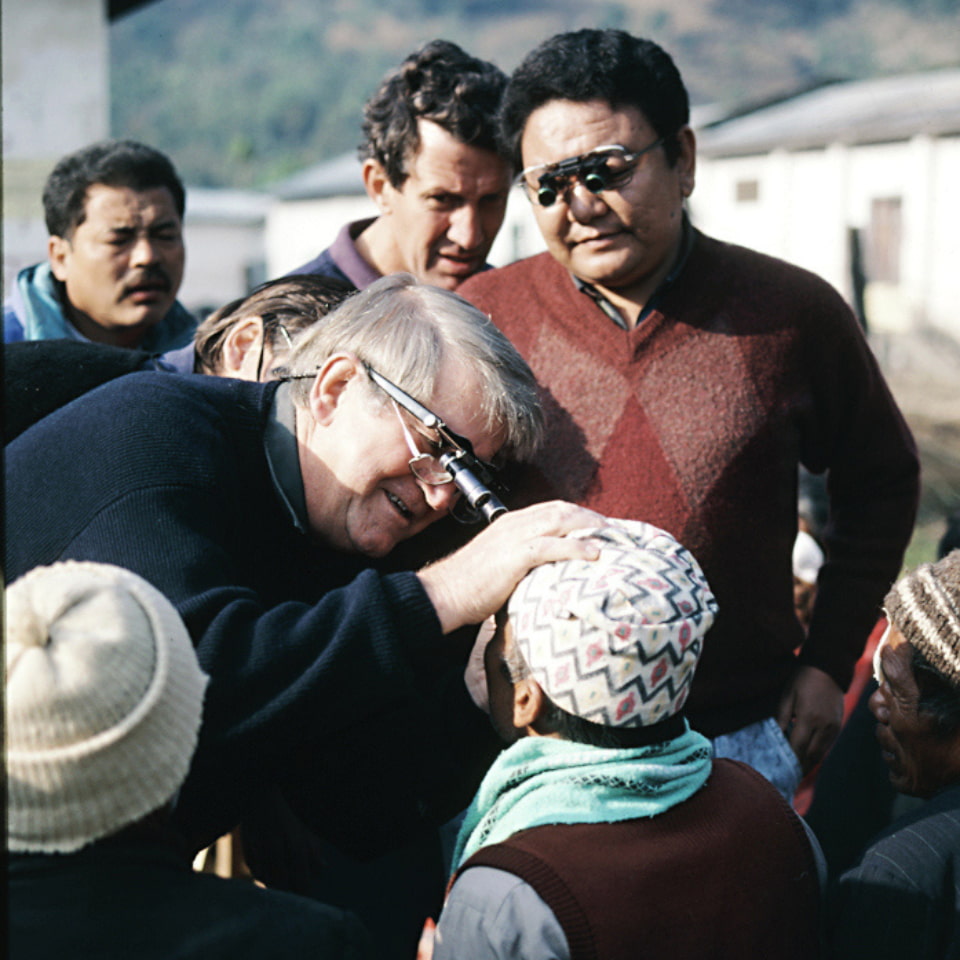

Fred and Dr Ruit

A friendship that changed millions of lives – and continues to do so today.

In 1985, Fred Hollows met a young Nepali doctor named Sanduk Ruit. That meeting would go on to change the future of eye health – not just in Nepal, but around the world.

Fred recognised Dr Ruit’s incredible skill and determination. The two quickly became close friends, bound by a shared belief: that everyone, no matter who they are or where they live, deserves the right to sight.

At the time, their ideas were considered radical. In 1989, Fred and Dr Ruit were criticised for daring to introduce modern cataract surgery in countries where the only option was outdated techniques that left patients with thick glasses and poor vision. But they refused to accept that people in poorer countries should receive second-class care.

Together, they helped pioneer low-cost intraocular lenses – a breakthrough that made cataract surgery more accessible to people living in poverty. Later, Dr Ruit co-founded the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology with support from The Fred Hollows Foundation.

Dr Ruit has since restored sight to more than 180,000 people.

But as he says: “This problem is not going to go away on its own. It takes people who are willing to stand up and say: I want to be part of the solution.”

With your support, we can continue their legacy and bring sight-saving care to people who need it most.