Why we're still fighting to end trachoma, 50 years on

A national program, a personal journey

My name is Trevor Buzzacott. I’m a proud Arabana man, and in 1975, I set off in a dusty old Land Rover with Fred Hollows and a small team of doctors, nurses and Aboriginal health workers. We were on a mission that would change the course of our lives — and the lives of thousands of people.

Together, we launched the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program, visiting hundreds of remote Aboriginal communities to tackle one of the most painful and preventable causes of blindness: trachoma.

Fred on top of a Land Rover in 1975, packed and ready as we set off to begin the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program.

Photo credit: Leon Cebon

We visited 465 remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, screened over 100,000 people, treated thousands for trachoma, and delivered more than 10,000 pairs of glasses. But more than that, we listened. We learned. And we worked side by side with communities which had been excluded from even the most basic healthcare.

It was never just about medicine. It was about justice, dignity and partnership. Fred believed that no one in this country should go blind from a preventable disease. And I still believe that today.

What is trachoma?

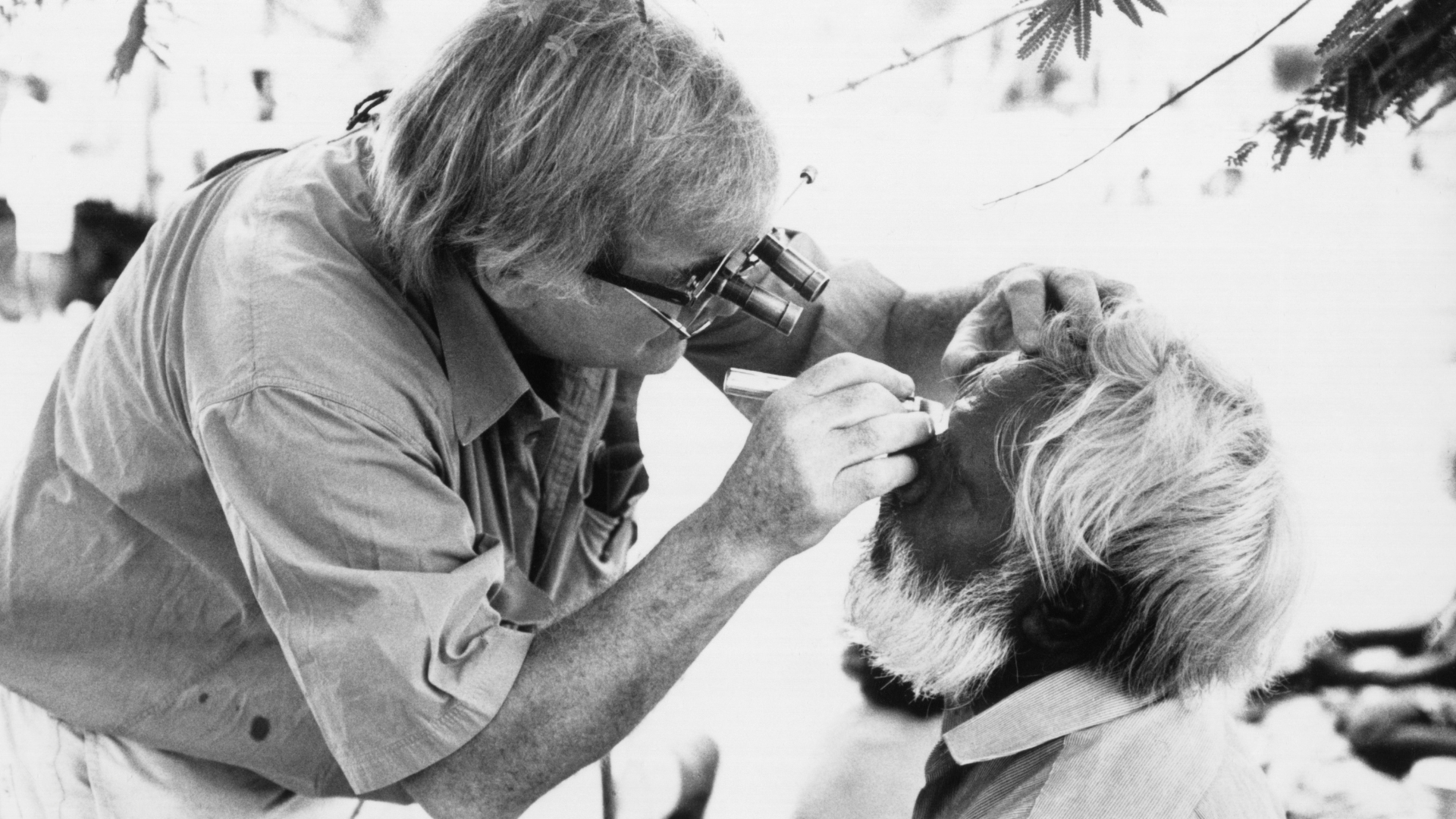

Fred Hollows with a patient during the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program.

Photo credit: The Fred Hollows Foundation

Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the world. It starts off like conjunctivitis — red, irritated eyes — but repeated infections lead to scarring that causes the eyelids to turn inward. The eyelashes scrape the eye with every blink, leading to intense pain and eventual, irreversible blindness.

In its later stages, people with trachoma often resort to pulling out their own eyelashes with tools just to ease the pain. It’s confronting. It’s heartbreaking. And worst of all, it’s preventable.

Trachoma is a disease of poverty

Trachoma thrives where people live without access to clean water, proper sanitation and adequate housing. It’s spread through dirty hands, shared cloths and flies that carry the bacteria from person to person. In overcrowded homes without working taps or functioning toilets, the cycle of infection becomes nearly impossible to break.

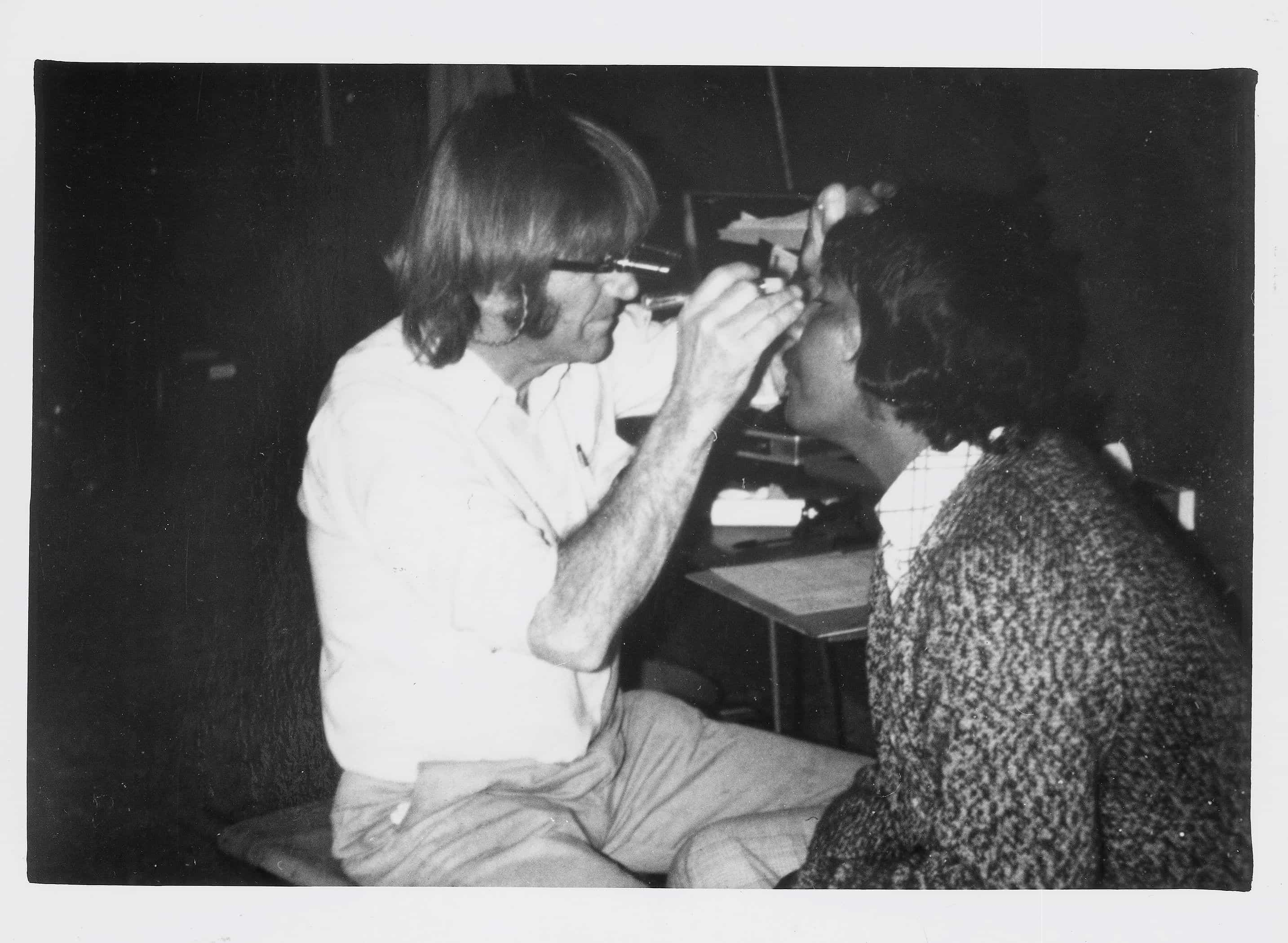

Women and children are most at risk. In many communities, women care for young children and are exposed to repeated reinfection, causing more severe damage over time.

Fred Hollows with a young Indigenous patient during the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program in the ‘70s.

Photo credit: The Fred Hollows Foundation

Today, 229 million people worldwide live in areas where they’re at risk of trachoma. In Australia, trachoma remains endemic in a number of remote Aboriginal communities, in the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia. Ours is the only high-income country where trachoma still exists as a public health issue.

Have we made progress in Australia? Absolutely.

After decades of tireless work, Australia has reached a major milestone. For the first time, all affected jurisdictions have reported trachoma prevalence in children aged 5–9 years below the World Health Organization’s elimination threshold of 5%.

It’s a huge achievement and a testament to the leadership of Aboriginal health workers, local communities, and the many partners working together to eliminate trachoma in Australia.

But elimination doesn’t mean eradication.

In several communities, trachoma is still present. The deeper causes — crowded housing, poor access to water and sanitation, and systemic neglect — haven’t been fully addressed. Without continued support, the disease could return.

What will it take to end trachoma for good?

The World Health Organization recommends the SAFE strategy, a globally recognised approach that’s proven to reduce trachoma rates:

- Surgery to correct inverted eyelashes in advanced cases

- Antibiotics to treat active infection and stop community spread

- Face washing to reduce eye-seeking flies and break the infection cycle

- Environmental improvements like clean water, sanitation and safe housing

The Fred Hollows Foundation is working around the world and here in Australia to implement these strategies alongside communities and governments. But the real key to long-term success is tackling the root causes of trachoma: poverty, inequality and a lack of political will.

Why this matters on World Day of Indigenous Peoples

Today, we honour the strength, resilience and leadership of Indigenous peoples around the world.

Here in Australia, I think of the mob who stood alongside Fred and me all those years ago — people like Jilpia Nappaljarri Jones, Rose Murray, Gordon Briscoe and Reg Murray — who helped make the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program what it was. Aboriginal liaison officers played a vital role, building trust and making sure our work was guided by the needs of community.

That sense of partnership, of listening and learning, is what made the program work. And it’s what still matters today.

I also think of the next generation of Aboriginal leaders continuing this legacy — people like Associate Professor Dr Kris Rallah-Baker. He’s Australia’s first and only Aboriginal ophthalmologist, and he’s helping to ensure that eye care for our mob is not only accessible, but culturally safe and community-led.

Dr Kris Rallah-Baker represents the next generation of Aboriginal leadership in eye health. Together, we’re carrying the legacy forward to finish what we started.

Photo credit: Michael Amendolia

Fifty years on, I know Fred would be proud of the progress we’ve made. But he’d be pushing us to go further. He’d be lighting a fire under us to finish what we started.

A legacy worth finishing

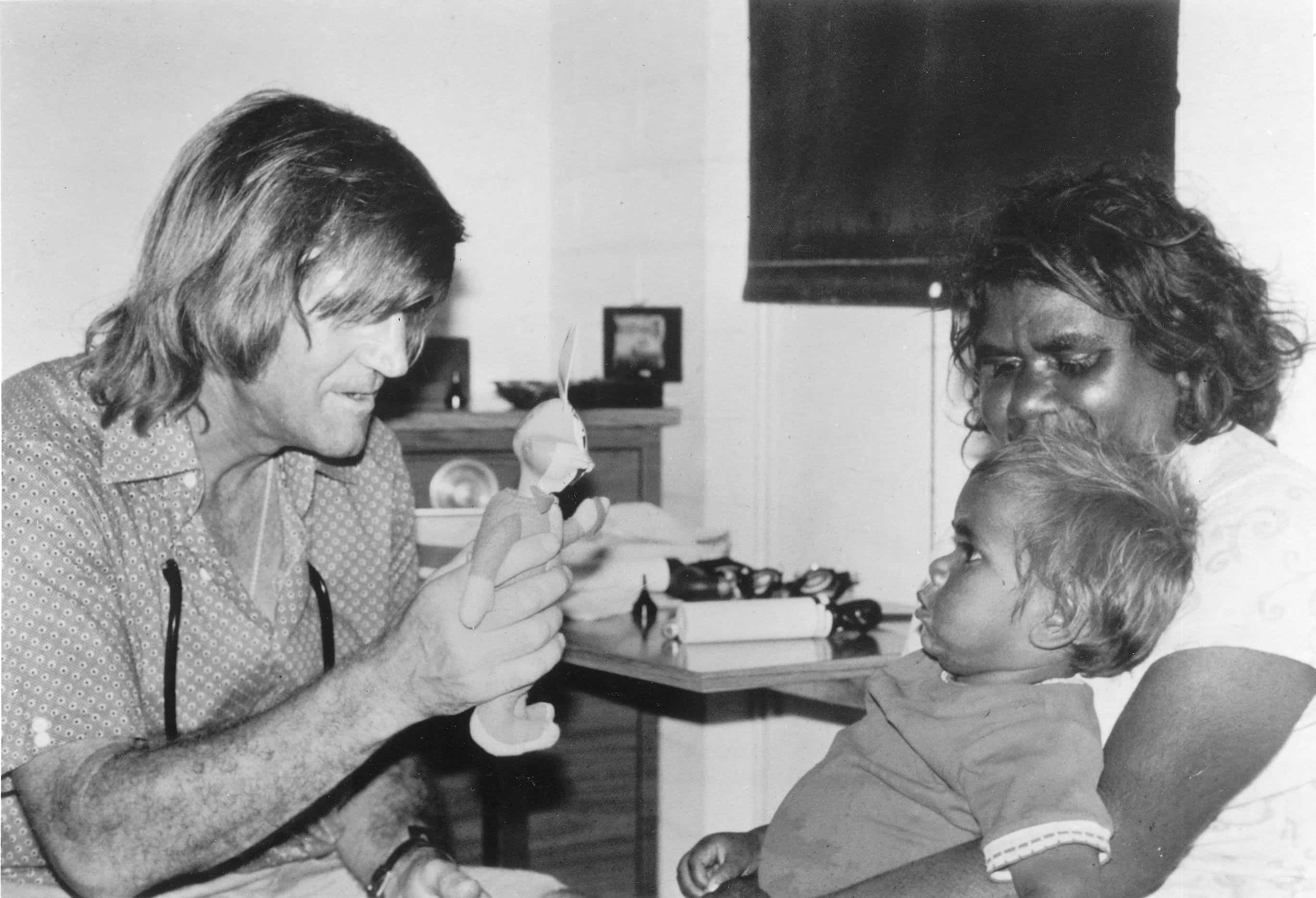

Gabi, Penny Luck and Fred Hollows at Christmas Creek in 1977, during the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program. We were part of something bigger than ourselves — working alongside communities to tackle a disease that should not have still existed here.

Photo credit: David Broadbent

It’s been 50 years since Fred, Gabi and I first hit the road. I reckon he’d be proud of how far we’ve come, but he’d be telling us to keep going.

And he’d be right.

I’m still in this fight because the job’s not done. No person in Australia — or anywhere else — should go blind from a disease we know how to prevent.

With the right support, the right leadership and the will to see it through, I believe we can end trachoma, not just as a health problem, but from history.

Meet the author

Related articles

5 Things You Can Do To Close The Gap

How to be an ally to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples