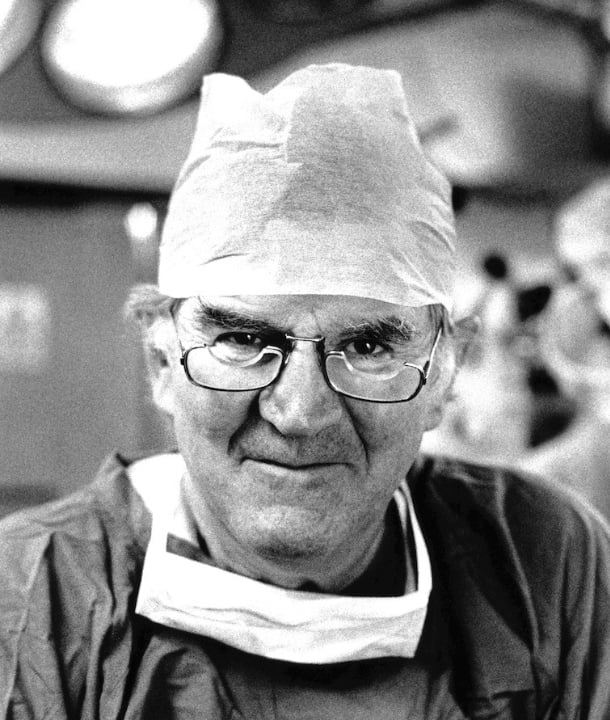

30 years ago, The Fred Hollows Foundation began a global movement to end avoidable blindness

Inspired by our founder, Professor Fred Hollows—an Australian eye surgeon and humanitarian who believed in empowering people to help themselves—we’ve restored sight or prevented blindness for over 150 million people worldwide. Fred’s vision was to eliminate avoidable blindness, and with our partners by our side, it’s a vision we can achieve.

Today, 9 out of 10 people who are blind or vision impaired don’t need to be. Many people stay needlessly blind because they live in poverty. In low- and middle-income countries, blindness denies people education, independence, and the ability to work—opportunities that can break the poverty cycle.

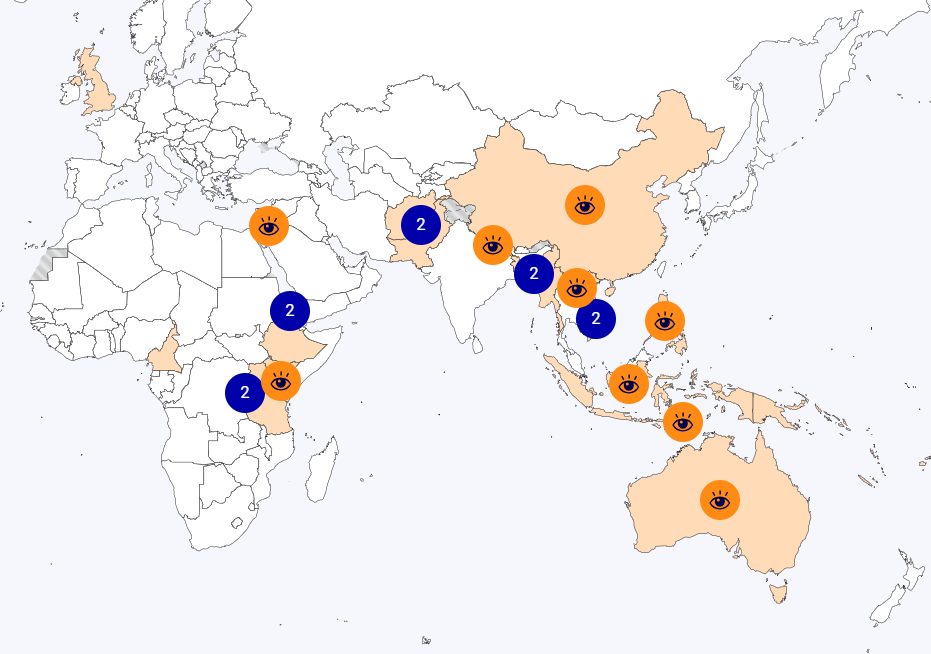

In more than 25 countries, we work with governments and partners to strengthen eye health systems, break down barriers to care, and train local eye care professionals to reach those in need.

We see a world in which no person is needlessly blind or vision impaired. With the support of our partners in 2023, our global impact was profound.

4,435,157

People screened.

612,376

Eye operations and treatments performed.

154,476

Pairs of glasses distributed.

36,804

People trained including community health workers, teachers, and surgeons.

A vision for change

The eye health crisis

Right now, 1.1 billion people are living with vision loss that could have been prevented. The demand for eye care is growing rapidly, outpacing even the best efforts. This crisis hits the most vulnerable the hardest: those living in poverty, in remote areas, women and girls, and the elderly.

How we're tackling it

We’re focusing on a big-picture approach—investing in research and technology, training healthcare workers, and partnering with governments to make eye care accessible to everyone. By addressing the root causes of vision loss, we’re not just treating blindness—we’re preventing it.

Who is helping us

We’re proud to work alongside a network of dedicated partners, including governments, NGOs, and local communities, who share our vision of eliminating avoidable blindness. These partners help deliver eye care to those who need it most, making our work more accessible and effective.

We're bringing eye care to all

Across more than 25 countries, we’re partnering with governments and local communities to build strong, sustainable eye health systems. Our work focuses on removing barriers to care and training the local workforce to meet the urgent needs of those with vision impairment.

Our mission is clear: to ensure that everyone, no matter where they live, has access to high-quality, affordable eye care. We believe that sight should never depend on where you were born.

But our work is far from over. Around 1 billion people globally are living with vision impairment that could be prevented or treated, including 43 million who are blind.

Every eye is an eye. When you are doing the surgery there, that is just as important as if you were doing eye surgery on the prime minister or the king.